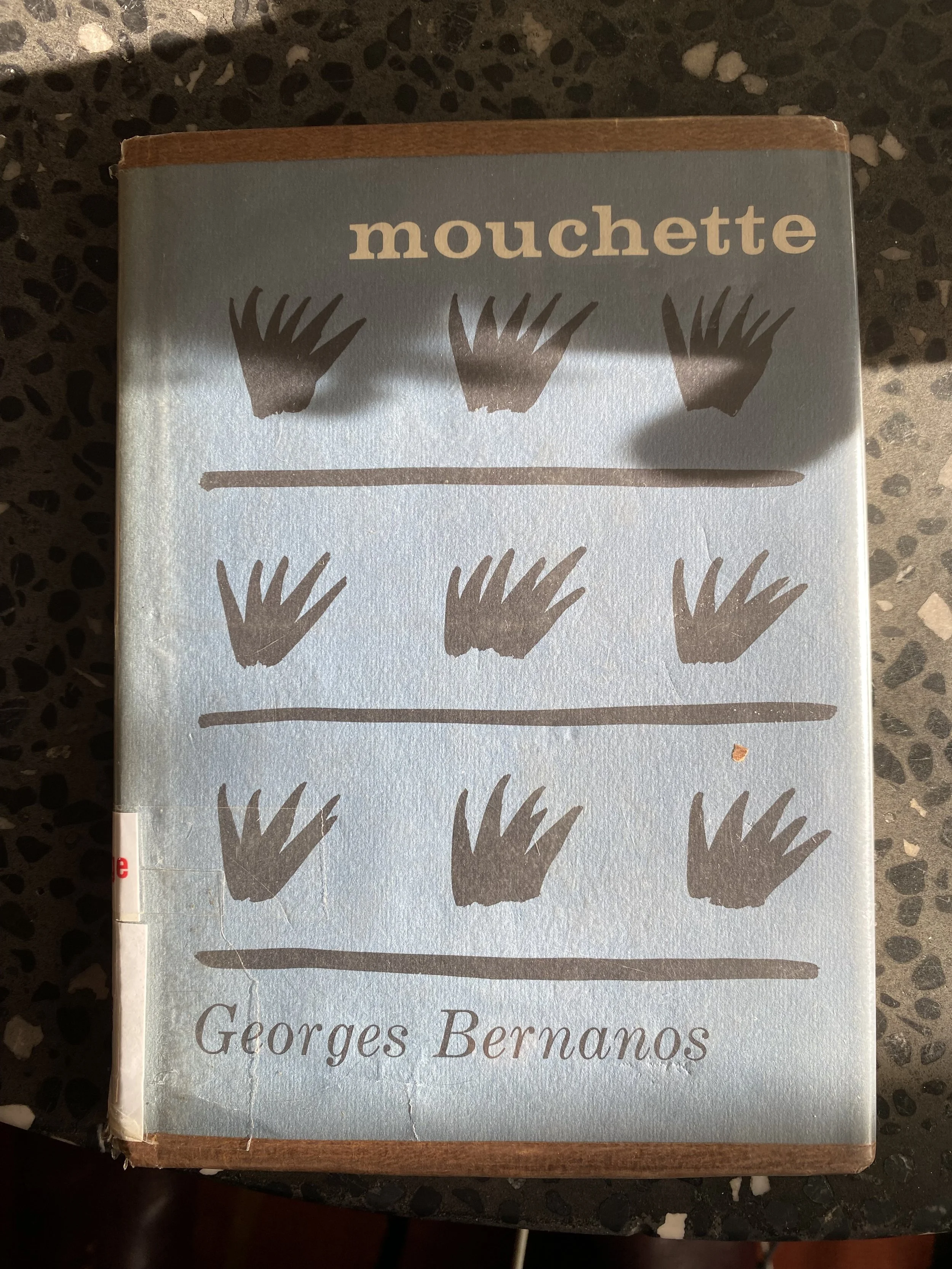

Mouchette (1937) is a slender novel of 127 pages that packs more vividness and understanding of human relationships than novels three times its size. Georges Bernanos’s achievement lies in showing the terrible yet seemingly inevitable way poverty governs behavior, emotion, and even the imagination. Its unflinching bleakness forces readers to confront their assumptions about who is deserving of sympathy and understanding. Class rage fuels the novel’s power.

The titular protagonist is a French peasant girl whose name means “little fly.” Mouchette is likewise a pest to the people around her. Scrunched up and defensive, sullen and brooding, the fourteen-year-old clomps around the village in her older brother’s too-big clogs.

With her terminally ill mother on her deathbed, Mouchette is left to tend to her neglected baby brother, who lies in soggy-blanketed filth, howling for care that never comes. Mouchette’s parents are alcoholics, and the family lives in squalor. Her bootlegger father demonstrates “a kind of stupid stubbornness” while her mother bears “the whole weight of their poverty, the symbol of their shared misery and its occasional humble joy.” She drinks to numb the pain, dribbling gin down her chin and telling Mouchette to top off the bottle with water so her father won’t notice. Doctors offer little relief for what ails her. They “were like vets—they cost a lot but all you got in return was a lot of words.”

Words have little value in the little village. “Lying had never seemed wrong to Mouchette,” Bernanos writes, “for it was the most precious—probably the only—privilege of the wretched.” She chooses gestures rather than words to express her rage, but even this proves ineffectual. Scorned by her classmates, she hides in the bushes after school to hurl mud at them. It “fell noiselessly on the road, and they did not even turn around.”